by DANIEL SOLYMARI and SARA GIBARTI

In Syria the conflict started in 2011 led to a countrywide realignment in both territorial and demographic traits with catastrophic consequences for the population. More than 6.6 million people were forced to leave their homeland, and a further 6.9 million became Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). Lately, a subsequent consolidation of the population ensued, which witnessed a partial self-repatriation of IDPs. In the Journal of Regional Security we have reported the preliminary results of a study to explore migration motives in the framework of the repatriation aid programme provided for these IDPs (Solymari and Gibarti 2023, 97–120). The analysed programme was coordinated by the Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Homs in and around the city of Homs. In the article we provided an overview of the geographic territory covered by the initiative and of the relevant events of the conflict which affected IDPs from the region. Key results from our analysis included the observation that individual experiences of traumatization and deterioration of social status are major contributing factors that fuel resettlement. Our work casted valuable light on the triggers of internal migration and timely guidance to ongoing struggles and newly emerging conflicts such as that of Ukraine in 2022. In this article we summarise some elements of the mentioned work.

The crises of flight and migration, of external and internal movements between countries and continents, are still among the most serious and complex social problems of our time. There is now a library of literature on the subject, the ‘refugee question’ has been at the forefront of international and media attention for many years, and political and social leaders seem to be redoubling their efforts to find the best solutions to alleviate the problem. Yet, more than ten years after the outbreak of the Arab Spring, the present remains fragile and the future uncertain throughout the world, but especially in many countries in North Africa and the Middle East. In Western Sahara, atrocities are once again a daily occurrence; the situation between Morocco and Algeria has escalated; Tunisia is in a state of political instability; Libya has not seen an easing of one of the most serious internal conflicts in the macro-region for years; Lebanon is on the brink of political and economic collapse; In Syria, ten years after the outbreak of perhaps the most serious war of our time, we are witnessing renewed fighting and a devastating earthquake; in Iraq, the Islamic State remains active and internal political unrest is not abating.

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched an operation against Ukraine, the most serious military conflict in Europe since the Second World War. Not to mention the crisis between Palestine and Israel, or the security and humanitarian challenges in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. This geopolitical picture is reflected in the numbers. Since 2010-2012, the number of internally displaced people has been steadily increasing. According to UN figures for 2021, this amounted to nearly 90 million people, double the number ten years earlier and the highest since World War II. And according to the latest UNHCR report for 2022, the number of displaced persons has exceeded 100 million. Refugees for religious reasons is a specific aspect of the issue, with the number of persecuted Christians alone estimated by specialist organisations at over 360 million; that is, one in seven Christians suffer physical abuse or psychological discrimination because of their faith.

The war in Syria began in March 2011 as an outgrowth of the broader Arab Spring protests that gripped an expanse reaching from North Africa to the Levant and beyond. Within the Syrian milieu of the Arab Spring, what began as demonstrations of discontent with the Syrian government quickly escalated into widespread armed revolt. After more than ten years of conflict, a huge range of elements of the crisis in Syria has been studied and subsequently reported in the academic literature. The overwhelming majority of these studies, however, variously deal with the complex interconnected geopolitical, diplomatic, or security policy-related issues of the war (Önis 2012; Phillips 2016; Hinnebusch and Saouli 2019; Daoudy 2020; Csicsmann and Rózsa 2022).

In this complex and fluid framework of social upheaval, the events in Syria are now well-understood to encompass a multifaceted local and international context with a particularly significant human component of suffering and resultant internal displacement. This latter element, i.e., internal migration, however important it is to understand in the context of humanitarian aid, has generally escaped analysis because the most emphasis has previously been placed on those who seek refuge well beyond the borders of their homeland.

In our analysis, we found that academic literature and international organizations’ reports addressed many aspects of the complex issue of internal migration, repatriation, and humanitarian assistance alongside with socioeconomic situation of IDPs regarding previous years’ conflict zones (Chowdhury 2000) and the Syrian crisis as well (Thibos 2014; Sert 2017). On the other hand, migration motivations of IDPs, in general, remain underrepresented and unrecognized in the international dialogue. We attribute this to a lack of first-hand, local reports as well as a certain level of disbelief that people would remain in the face of such terrifying hardship.

The primary objective of the mentioned paper was to discuss and analyse the social and humanitarian challenges faced by Internally Displaced Persons (hereinafter IDPs) in the city of Homs, their main motivations for migration and the circumstances of their displacement. It does so first and foremost by analysing interviews with IDPs involved in the repatriation programme mentioned above. In order to provide a descriptive context, the study also looks at the situation of Homs and the evolving overall circumstances of internal displacement in Syria during the war. We have to highlight that the study focuses consistently on the plight and needs of IDPs within the Syrian border, for which years of research and active engagement in lending assistance are at hand.

Our overall goal is to gain a more accurate understanding of the daily struggle of internally displaced people during the different phases of the war and thus form a more holistic view of the impact of such displacement on Syrian society. The significance of the analysis of the IDPs further lies in the fact that while many (due to lack of financial and other resources) persons did not leave their country, a significant number of them remained in their homeland as a result of their own, personal decision to remain and invest in the recovery of their land.

Our research has shown that the reason for this decision was not only to avoid dangerous international migration routes but also the intent to continue residence in Syria. In our analysis, we share what we have found about the motivations that compel millions of people to migrate to destinations within the zone(s) of conflict. The purpose of our writing is not to accurately reconstruct the antecedents and events of the Syrian conflict or to give a detailed narration of the political history aspects of the conflict. Instead, it is directed at describing the local and international actors’ system of relations and to use this information to both understand the sentiments of IDPs and in doing so, guide aid efforts.

In our pilot research, we visited fifty internally displaced refugee families and interviewed them in accordance with the guidelines of an in-depth interview. Our goal was to make it easier to comprehend the deep, personal side of the phenomenon, the motivation of migration and thus the complexity of migrations and (highlighted with a special emphasis) to ensure that the families participating in the repatriation program are given better assistance that is based on community involvement.

The IDP community in Syria constitutes the primary client base of development aid. According to the estimated data of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, currently 6.9 million IDPs are living in Syrian territory (UNHCR 2022). This data comprises one of the world’s largest populations of its kind, yet their safety and particular challenges appear under-represented in the professional and academic discourse alike. Indeed, the relative paucity of reports on the plight of this category of displaced persons is in contrast to the widespread attention directed towards refugees crossing external borders, and the entirety of processes and problems pertaining to them (Harpviken and Yogev 2016).

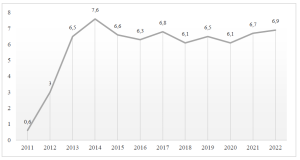

However, similarly to the number of people fleeing to destinations outside of Syria, the number of IDPs has also undergone rapid growth as an aftermath of the wave of violence that unfolded in March 2011 (International Displacement Monitoring Centre 2012). Data show (Chart 1) that with the escalation of the armed conflict, both global and regional powers joined in the active conflict, then with the so-called Islamic State gaining ground, the number of IDPs rose at such a rate that by the end of 2014, already 7.6 million of them lived in Syria as refugees without crossing the country’s borders (International Displacement Monitoring Centre 2019). The spectacular decrease in 2015, which is also visible on the chart, does not primarily reflect greater rates of returning home or resettling but rather the mass-scale domestic displacement wave that evolved into the flow of refugees from Syria, directed towards the territory of Turkey and beyond, to the European Union.

Regarding the numbers in the chart below, it must be noted that they indicate mainly estimated and approximate data, which is a common challenge in other aspects of the humanitarian crisis caused by the Syrian conflict as well. This lack of accuracy is due not only to the country’s barely accessible conflict areas, the encircled settlements, or the absence of international humanitarian organisations, but also to the fact that the Syrian government made data collection extremely difficult by not officially acknowledging the presence of IDPs in the country (Ferris and Kirişci 2016).

Chart 1: Evolution of the number of IDPs (in millions of persons) in Syria between 2011 and 2022 (IDMC 2019, OCHA 2020, UNHCR 2022)

Despite academic papers highlighting and assessing the psychological challenges of refugees and war populations (both in Syria and other armed conflicts) (Kaplan 2009; Nickerson 2011), certain aspects of this issue are still unknown. According to Aarethun et al. (2021) “we know little about the mental triggers of forced migration, in order to be able to offer these people appropriate help. We need the greatest possible knowledge about how their mental problems could be defined, in what manner these could be best treated” (Aarethun et al. 2021). The survey in the study mentioned here, which was carried out with the vignette method, investigated the extent to which PTSD can be observed among Syrian refugees. In its findings, the survey stresses that “…besides depression, PTSD is markedly frequent among the refugees” (Aarethun et al. 2021). The survey concluded that severe pre- and post-migration trauma can be observed among both women and men – even though, as they put it – it is important that these symptoms do not necessarily constitute mental disorders.

The Syrian part of Gallup World Poll’s worldwide assessment made identical statements. Their research, which they carried out between 2008 and 2015, and then published in 2020, is one of the latest large-sample surveys in a Syrian context (Cheung et al. 2020). This assessment analysed the impact of the armed conflict on social welfare, and thus, naturally, it did not deal with social-type questions such as migration motivation, the root of persecution and better disclosure of its causes.

The decade of the Syrian war brought about a significant territorial and demographic realignment, along with a profound structural and economic crisis that was a calamity for the people affected. Anyone heading to the city from Damascus Airport – which is operating international traffic again – or on their way to Homs or perhaps East Aleppo will catch sight of razed city neighbourhoods and quarters. These areas were bombed to the ground. Considering the extent of the destruction, it seems to be impossible to rebuild, rehabilitate these districts and buildings, and realistically expect the former residents to return to live here. The extended war is perhaps over (maybe just for the time being), but due to the lack of basic services and the internal instability, it is a real challenge to launch effective repatriation processes. Even though some forms of dialogue have begun, no Syrian governmental support is in sight yet to promote these processes. The commitment of international donors is, at present, insufficient for solving the problem efficiently. It is our view that what we have learned in our work with internally displaced persons in Syria is not unique to that particular location but helps us to guide our aid efforts to provide aid to emerging flashpoints, such as Ukraine.

As opposed to the mainstream discourse, it is evident from our analysis that the concept that all refugees wish to settle down in Western Europe is erroneous. The majority, especially the IDPs, eagerly await the opportunity to return home. This conclusion is overlooked by most aid organisations, and we wish to add this fact to the discourse on how best to implement relief for those who need it. Fulfilling their wishes means we understand that it is necessary for them that we help them return home, thus creating a realistic chance of a new start. Aggravating circumstance in this work is that the status and judgment of the local actors in dialogue with the implementers are in constant flux, and the assessment of the results is not clear. Only one thing is certain: the duty to help the vulnerable civilian population in need by helping them rebuild their lives with dignity and security.

References

Aarethun, Vilde, Gro Sandal, Eugene Guribye, Valeria Markova, and Hege H. Bye. 2021. “Explanatory models and help-seeking for symptoms of PTSD and depression among Syrian refugees.” Social Science & Medicine 277: 113889.

Cheung, Felix, Amanda Kube, Louis Tay, Edward Diener, Joshua J. Jackson, Richard E. Lucas, Michael Y. Ni, and Gabriel M. Leung. 2020. “The impact of the Syrian conflict on population well-being.” Nature Communications 11 (1): 3899.

Chowdhury, Jamil. 2000. “Reintegration of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) – The Need for Micro-credit.” Refugee Survey Quarterly, 19 (2): 201–215.

Csicsmann, László and N. Rózsa Erzsébet. 2022. “Authoritarian Resilience and Political Transformation in the Arab World: Lessons from the Arab Spring 2.0.” International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 15 (1): 3–30.

Daoudy, Marwa. 2020. “Water Weaponization in the Syrian Conflict: Strategies of Domination and Cooperation.” International Affairs 96 (5): 1347–1366.

Ferris, Elizabeth, and Kemal Kirişci. 2016. The Consequences of Chaos – Syria’s Humanitarian Crisis and the Failure to Protect. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Harpviken, Berg Kristian, and Benjamin Onne Yogev. 2016. “Syria’s Internally Displaced and the Risk of Militarization.” PRIO Policy Brief. Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Hinnebusch, Raymond, and Adham Saouli, eds. 2019. The War for Syria – Regional and International Dimensions of the Syrian Uprising. London: Routledge.

International Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2012. A full-scale displacement and humanitarian crisis with no solutions in sight. IDMC. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/syria-brief-aug2012.pdf.

International Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2019. A decade of displacement in the Middle East and North Africa. IDMC. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/IDMC_MenaReport_final.pdf.

Kaplan, Ida. 2009. “Effects of trauma and the refugee experience on psychological assessment processes and interpretation.” Australian Psychologist 44 (1): 6–15.

Nickerson, Angela, Richard A. Bryant, Derrick Silove, and Zachary Steel. 2011. “A critical review of psychological treatments of posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees.” Clinical Psychology Review 31 (3): 399–417.

OCHA. 2020. Humanitarian Needs Overview – Syrian Arab Republic. OCHA. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/syria_2020_humanitarian_needs_overview.pdf.

Öniş, Ziya. 2012. “Turkey and the Arab Spring: between ethics and self-interest.” Insight Turkey 14 (3): 45–63.

Phillips, Christopher. 2016. The Battle for Syria – International Rivalry in the New Middle East. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sert, Deniz S. 2017. “Turkey’s Position on IDP Properties: Lessons (Not) Learned.” International Migration 55 (5): 150–161.

Thibos, Cameron. 2014. “Half a Country Displaced: The Syrian Refugee and IDP Crisis.” IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook 2014. Accessed December 18, 2022. https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Half-a-Country-Displaced-the-Syrian-Refugee-and-IDP-Crisis.pdf.

UNHCR Syria. 2022. Syria Key Figures: January-September 2022. UNHCR. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://reporting.unhcr.org/document/3682.

Daniel Solymari, University of Pécs, Political Science Doctoral Programme, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Solymari studied Theology and International Relations in Hungary and in the United Kingdom and holds MA degrees. He has received an advanced degree in Humanitarian Diplomacy at ICRC. He researches and writes on a number of issues in the area of international aid, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and migration and re-settlement initiatives. Daniel is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Pécs. Solymari works as a researcher, a diplomat and a head of department in Hungary and in Syria and in Jordan.

Sara Gibarti is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Regional Studies, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies in Hungary. Sára holds a BA and MA in International Relations and a PhD in Political Science. Her research area focuses on theories and practices of international aid, evolving trends in humanitarian food assistance, protracted forced displacement and humanitarian situations, alongside the Syrian refugee crisis and Turkey’s refugee policy.

You can also read: “Migration motivation and psychosocial issues of Internally Displaced People: A close-up from Homs, Syria”, by Daniel Solymari and Sara Gibarti (in Journal of Regional Security 18 (1): 97–120)

Photo credit: Images of hope in murals in the city of Homs, Syria, painted in 2015 during the war that that started in 2011 and devastated the country. Amgad Beblawi, Wikimedia Commons.