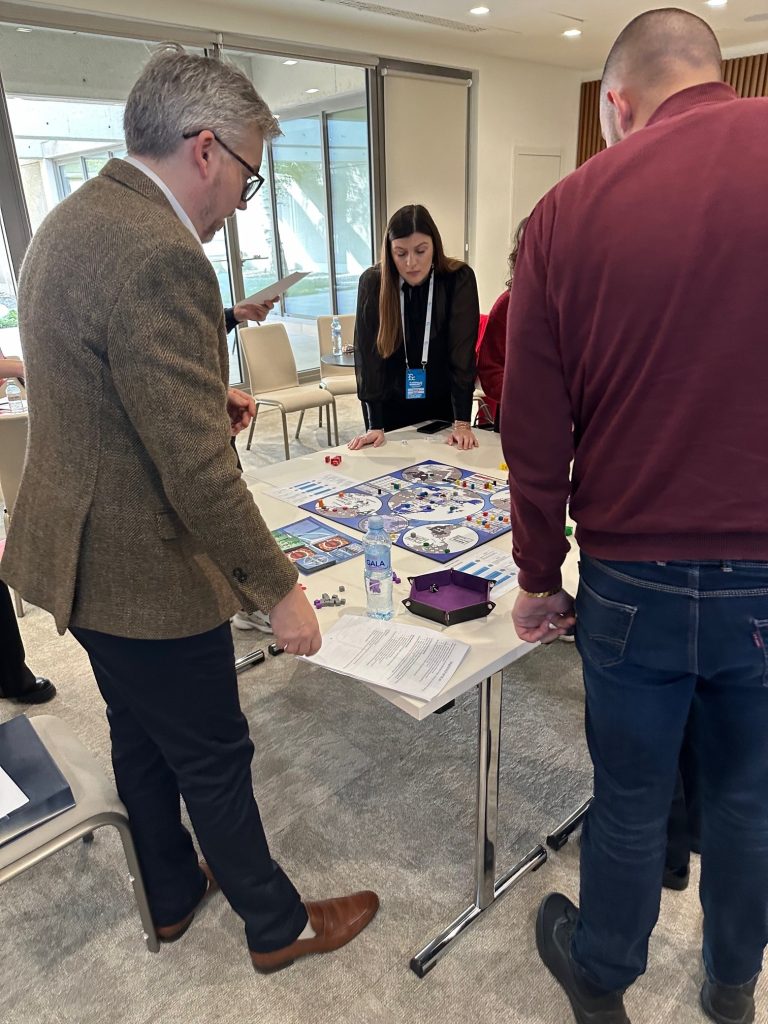

Dr David Banks, Senior Lecturer in Wargaming at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, attended the Belgrade Security Conference 2024 where he on 18 November held a gaming session featuring the serious game called “Horizons”. During the game, the conference participants engaged in an innovative learning approach using board games, a method that has gained recognition at top global universities but remains underutilized in the region. They collaborated with professors from the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Belgrade and experts from King’s College London, who facilitated game sessions focused on regional security cooperation. “Horizons” is a strategic board game where participants take on the roles of NATO, the EU, the USA, China, and Russia between 2024 and 2045, making decisions in political, military, economic, and technological spheres. CIS-FPN intern Marija Boričić interviewed Dr Banks during the conference. You can read the full interview below:

Dr Banks, can you tell us what we are doing here at Belgrade Security Conference?

Our participants here play a game that I was the lead designer in for NATO called Horizons, developed by the Wargaming Network as part of Wargaming Week that NATO ACT and Wargaming Network organize together. Many of the games NATO is running are classified, but we built a game which was unclassified, taking place in public, doesn’t represent the views of NATO, but the interpretation of the knowledge Kings Wargaming Network has. We built a game which would start in 2024 and terminate in 2045. It’s a game about NATO, the US, the EU, China and Russia and how they might compete or cooperate in a global space that includes the variety of different things that the players can do or have to be concerned about, including building of economic power, military bases, intervening or causing minor or major conflicts, nuclear proliferation, psyops, global populism, elections, regimes stability, climate change, etc. All games are, in my opinion, models, limited ones, and you cannot know how accurate they are, especially when you model anything that is not physical, non-kinetic, and once you leave behind battle space, missiles and explosions and start moving into politics, populism and regime stability. The way we built Horizons was we first created a game called Sleepwalkers, which was very open, with very few rules. The players would suggest lines of action, which they would judicate together. All the players were subject of matter experts, mostly from the Wargame department, from NATO, from other universities and the quality of the expertise in the room helped give us the contours what we needed to include in the final game. Then we built another game called Age of Confusion which had more rules, narrowed the scope of the game a little more, with a few key ideas, but players were still free to decide on their own. Combining the results of those games and our research, we build this rigid game. By rigid, that means a game in which all the rules are in the box, there is no interpretation, everything is in the manual – if you do this, this will happen – and the idea was we’d run the game a certain number of times and get data that the game generates, which is synthetic data, fake data about the future and NATO can use it as comparison as much or as little as they like.

You mentioned that the purpose of this game is data, but can you tell me more about what is the goal of wargames for players, and this game specifically for NATO players?

Yes, so that is a very good question, because I think the general agreement among both academics and professional wargamers is that a good game is a game that is clear of its own purpose. Our goal was to create a game that would generate data about global trends by 2045 with NATO as the central actor. Some might say that this game doesn’t make any sense or that the predictions are completely wrong. I would accept that criticism, except that the purpose of this game is not to represent what the world is going to look like in 2045, it is to represent how NATO would engage with the world in certain situations. It is different from educational games whose purpose is for players to get knowledge or entertainment games whose goal is for players to have fun. We like our participants to have a good time, but the priority is to compete against each other, use strategies and to collect synthetic data for analytical purposes.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of the rigid game?

The advantage of the rigid game is that the data is the same type of data repeatedly. For China to build a military base in Indonesia there must be the same preconditions in every game. What you have is data that you compare across all those games, because the only thing that’s varying are decisions the players are making. What isn’t varying is the type of decisions they are making, since there is a list of options that is quite long but is exhaustive, and if it’s not on that list of actions, they cannot choose it. In the end, there is comparable data across all those cases. Usually, most analytic games are run very few times, often once, and require a high level of expertise in the room, such as diplomats and ex-parliamentarians and star generals, which requires resources, and the question is if you could gather those people in the same room. The benefit of those games at the highest level is, because the rules are looser, anything can really happen. They act more creatively, based on the knowledge and experience they have. The output of the rigid game is based more on design and less on creativity of players. The way we compensate for that is by having the earlier stages of the game design be loose and working with people that are expert in their field, so we gather knowledge to create a model. It is not a perfect system, it has limitations, which are noted to NATO in the final report, so they know how to approach the data we collected.

From your experience, do NATO and other organizations take results seriously, and into consideration?

The answer is we don’t know. I can give you one example of the game RAND ran in 2016 called “Reinforcing deterrence on NATO’s eastern flank” and the goal was to see what would happen if Russia invaded the Baltics. They ran a game about 20 times, and in the best-case scenario from the NATO perspective, Russia occupied Talin in 60 hours. The game showed that there were no NATO forces in the Baltics and that Russia would take the Baltics first. About a year later NATO forward deployed to the Baltics. Now, did they deploy to the Baltics because of this game, we don’t really know. We know some people read it, we know some people made a big deal about it and said “Wow, look at this”. My position is that you cannot blame political scientists for the decisions politicians make. Maybe someone used the results of the game to justify the decision they have already made. There is an example in Ukraine, in the most recent offense back in spring, a story from the Washington Post about how they had wargame parts of that offensive, and when the offensive failed, part of the blame was placed on the wargame. That is more likely to occur than for games to get acknowledged. Which some of it is fair because wargames do model. RAND revisited that game from 2016 in the light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and they determined that the game wasn’t realistic. Most professional and academic wargamers agree that you shouldn’t use a game as a symbol and reason to make a decision, it is mostly for gathering data.

Can you talk about the difference between academic wargaming and professional wargaming?

Until very recently, there hadn’t been very much academic wargaming per se. Mostly it’s only been professional wargaming. Until the last 35 years, there hadn’t been very much literature thinking. There are some prominent books and articles from this field, mostly from the nineties, and professional wargamers were satisfied, since that is what they needed. When I entered this space, 8 years ago, I wasn’t sure about how some of this stuff works, and now that I’ve read everything, I realize actually it’s not as clear how wargames actually work. There’s not really that many academics in this space. I think a generous assessment would be 30, who are really focused on understanding how the game works, how you know you are building it the right way, how you know you are getting results that can be defended. The opinions are very fluid, but the general debate is that some academics think to make this rigorous, it needs to look as much as possible as an experiment. A classic experimental design, A/B testing, with highly rigid rules, the right people in the room run the game hundreds of times, compare a very narrow set of questions with each other, for a high level of statistical significance. I think, instead of saying “Everyone needs to do it this way”, let us understand how the games which were successful worked and why they worked. Let’s look at what professional wargames are doing and try to retreat the method as a thing itself that would have its own set of rules, its own set of principles that are different from experiments or statistics, or case studies. So that is the current debate.

What do you think the future for wargames is?

Currently, it’s super popular. It is like a sign wave; it goes up and down. In 2015, NATO and the US released nearly 600 million dollars for wargaming, and everyone in DC, every consultancy, came out and said, “Oh I will do it”. It got really popular, then all that money was spent, and I think a lot of people expected it to drop in popularity and that would be the end of it. But in fact, it’s just growing. More and more defense sectors are wanting games to be produced, and more and more consultancies are offering those services. It is growing and it is not clear why. My two most prominent hypotheses are that the strategic circumstances are so confusing right now, that I think there is an appetite for any form of forecasting. People are willing to accept a level of uncertainty of forecasting they wouldn’t accept 30 years ago, in a more stable world. People want to know what the future holds, so they are reaching out for any methods, not just wargaming, to find out something about the future. The other one, I think, is the fact that we’ve grown up as a generation that played games when we were young, and many of us didn’t give them up when we got older. We talk about people of 50 years or younger that are willing to accept gaming as a possibility, as a method in a way that wouldn’t be true for older generations. I believe it’s also a generational shift where the idea of a game is not childish or alien to a wider population in the world in general. When you talk about it, people are not weirded out as they would have been 30 years ago. But the answer is, we don’t know. I am waiting for the PhD student to apply and say “I want to write a PhD dissertation about why and how” and I will supervise him, because I want to know the answer too.

Interview conducted by Marija Boričić, CIS-FPN intern.