by NEMANJA DŽUVEROVIĆ

This year represents the year zero for the Balkan Peace Index (BPI). The Index represents

an effort to assess the quality of peace and to quantify peacefulness in the region that is

nowadays known by the politically coined term Western Balkans (see Petrović 2014) and

encompasses seven countries and territories: Albania, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina,

Kosovo*, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia.

The BPI is not the first peace index. There are many other indexes launched in previous

years, with the Global Peace Index2 being the most famous one. What makes the difference between the BPI and the rest of peace indexes (Failed States Index, Positive Peace Index, etc.) is that it is the first locally designed and locally owned peace index that tries to respond to the critique pointed towards peace measurement without understanding a local context or without consultation with the local population what peace means for them

(for the critique see Firchow 2018; Löwenheim 2007, 2008; Mac Ginty 2013a, 2013b).

The BPI was created by a team of researchers coming from the University of Belgrade

(Faculty of Political Science and Faculty of Organisational Sciences), and it is part of the

wider research project that aims to introduce ‘local turn’ (Mac Ginty and Richmond 2013;

Džuverović 2021) in peace measurement. The project bears the name Monitoring and

Indexing Peace and Security in the Western Balkans – MIND,3 and it is supported by the

Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia.

The starting point for the BPI is that quantifying and scaling the peace in the Western Balkans is not the only important step needed to understand peace dynamics in the region that only 20 years ago experienced the most violent conflicts in Europe after World War

II. Instead, what is equally important is to understand the quality of peace in the region

and to recognise the key ‘infrastructures of peace’ (Richmond 2013). Accordingly, the BPI

2022 does not aim (only) to rank the countries of the region (with one being more peaceful

than others) but to determine the quality and durability of peace in each of the countries.

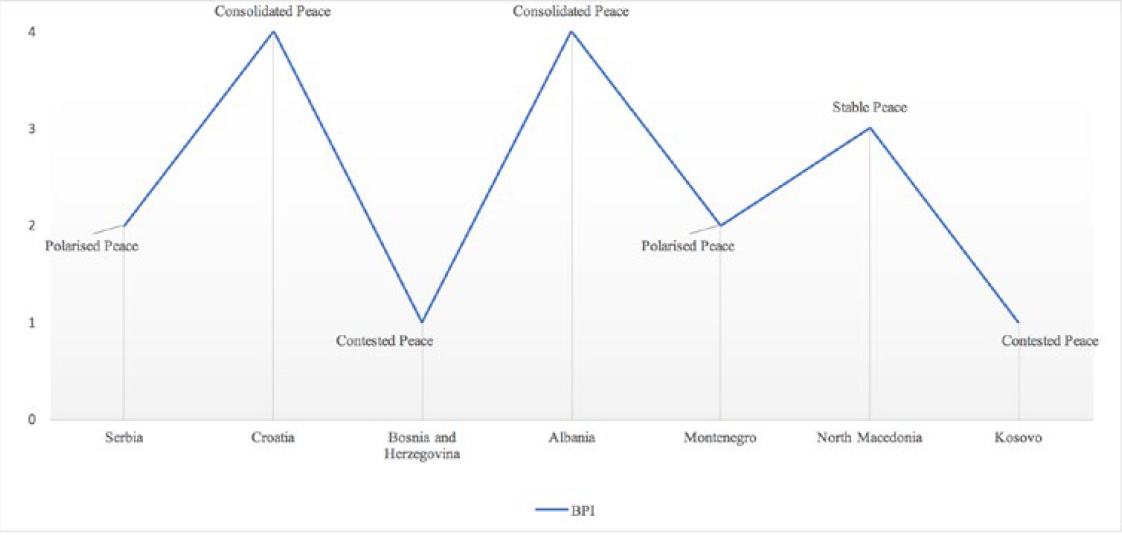

4 For the year 2022, Croatia and Albania are classified as countries with consolidated

peace, followed by North Macedonia (Stable Peace), Montenegro and Serbia (Polarised

Peace) and Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo (Contested Peace).

Figure 1: BPI 2022

Balkan Peace Index 2022

The BPI consists of seven domains, with each of them having three or more indicators and

sub-indicators (Appendix 1). On the side of ‘negative peace’ are two domains (Political

Violence and Fighting Crime), while on the side of ‘positive peace’, there are five domains:

Regional and International Relations, State Capacity, Socio-Economic Development, Political

Pluralism, and Environmental Sustainability. Out of these seven domains, Western

Balkan countries in 2022 performed excellently in only one domain – (lack of) political

violence. At the same time, most of them gained poor scores in environmental sustainability and fighting crime and average scores in regional and international relations, state capacity, political pluralism, and socio-economic development. Overall, the region can be considered peaceful in terms of negative peace or the absence of armed violence, but the level of positive peace remains between poor and average.

So, what does Balkan Peace Index 2022 tell us about the peace in the region in the previous year? In a nutshell, the Western Balkans could be regarded as a peaceful region. It has been free of armed conflicts for more than twenty years now. Although still burdened by the 1990s war legacy and political and ethnic conflicts, it displays low levels of political

violence. In 2022 only Kosovo was affected by the violent crisis (this continued throughout

2023), while all other countries in the region, including the highly polarised Bosnia

and Herzegovina (BiH), experienced political disputes or non-violent crises. Still, Kosovo

and BiH remain neuralgic issues in the region. Both are cases of permanent political crisis

since the sovereignty of the former is contested from the outside, while the sovereignty of

the latter is disputed from the inside. Clashes between the Albanian majority and Serbian

minority in Kosovo, the Serbian and Kosovo government, or between Republika Srpska

and the central government in BiH, and Croatian and Bosniak representatives in the Federation of BiH, are the main causes of instability in the region. Although long-lasting

crises, these two cases have little potential to escalate into limited or full wars. The main

reason is the presence of international peacekeeping forces that can contain the possible

spread of violence.

You can continue reading the full article in Journal of Regional Security.

* This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia [grant number 7744512] Monitoring and Indexing Peace and Security in the Western Balkans – MIND.

Nemanja Džuverović is a professor in Peace Studies at the University of Belgrade. His research areas include critical peacebuilding, political economy of liberal peacebuilding, international statebuilding in the Balkans, and sociology of International Relations. In 2020 he was Visiting Fulbright Scholar at Northwestern University. He has been visiting researcher at the University of Manchester (Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute), the University of Uppsala (Department of Peace and Conflict Research), the University of Bradford (Department of Peace Studies and International Development) and the University of Granada (Institute for Peace and Conflicts). Nemanja has also been a visiting professor at several universities, including University of Konstanz, University of Bologna, University of Granada, Masaryk University, University of Zagreb, and University of Warsaw. He is co-editor of the Journal of Regional Security and the program director of MA Peace, Security and Development.